While generational resilience and resistance in the United States has been in my blood for four generations, like most immigrant families, my family never spoke about the past. It would conjure up too much tragedy, loss, and trauma that has been buried for years. This act of forgetting is common. We want to forget our past, our memories, our struggles, and hardships. I, however, long for those memories I don’t have access to. As my grandparents and ancestors have passed on, the tools I have available to me are the fragmented stories that have been orally passed on and activated in my imagination. These forgotten stories not only honor my ancestors’ past, but also allow me to live in the present.

It was only three years ago, when I sat down with my father to document our family’s story, that I started to understand the depth of our family’s roots in the United States, where European nativists (settlers) have done all they could to chase away my Chinese ancestors. “Your great-grandfather immigrated to Reno, Nevada to work,” my dad told me. “Wait. What? I had no idea. When was he here? What kind of work did he do?” I asked. “It’s all fuzzy. But we think maybe a hand laundry business. In the late 1800s,” dad replied. My great-grandfather’s story is similar to other Chinese immigrants, who came to the US hoping to build roots and find the “golden mountain.”

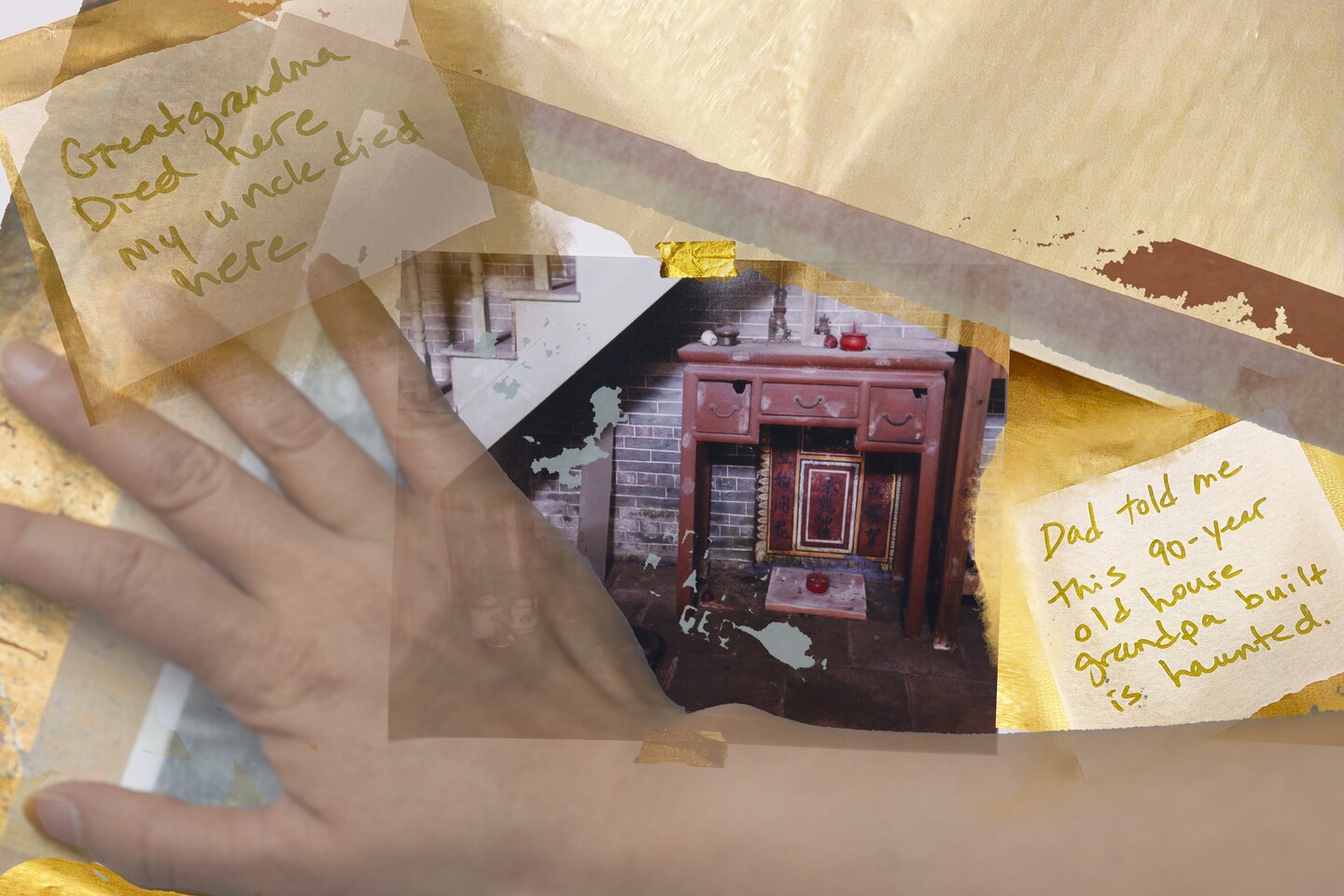

The shrine in the author’s family house back in China, dating back eighty-five years. Image by Betty Yu, 2017/2020.

Notes on Exclusion

Like many immigrant and communities of color, the history of systematic discrimination in the United States against people of Chinese descent was brutal and driven by white nationalism. The racist and xenophobic 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which prohibited more than a few hundred male merchants to come to the US, remains the only law to have been implemented by the government of the United States preventing members of a specific ethnic or national group from immigrating to the country. My own family’s story is not unique, but it is a testimonial of the history of dispossession of land rights, denial of citizenship to non-European immigrants and enslaved people, and white supremacist/nativist ideology that the US was built on.

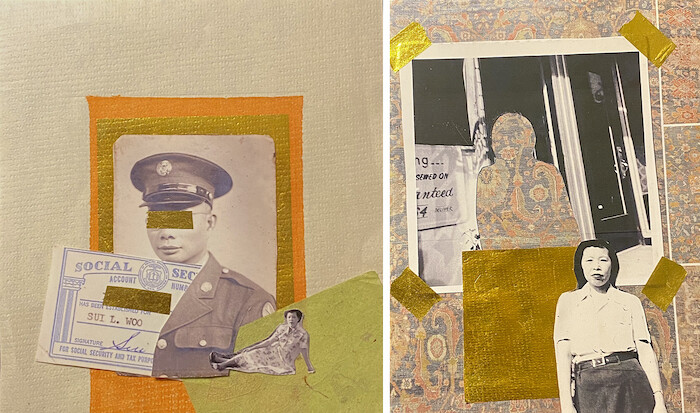

Left: The author’s grandpa served in the US military during WWII, while the Chinese Exclusion Act was still in place; the author’s grandma came to the US later. Right: The author’s grandma in front of their hand laundry business. Images by Betty Yu, 2021.

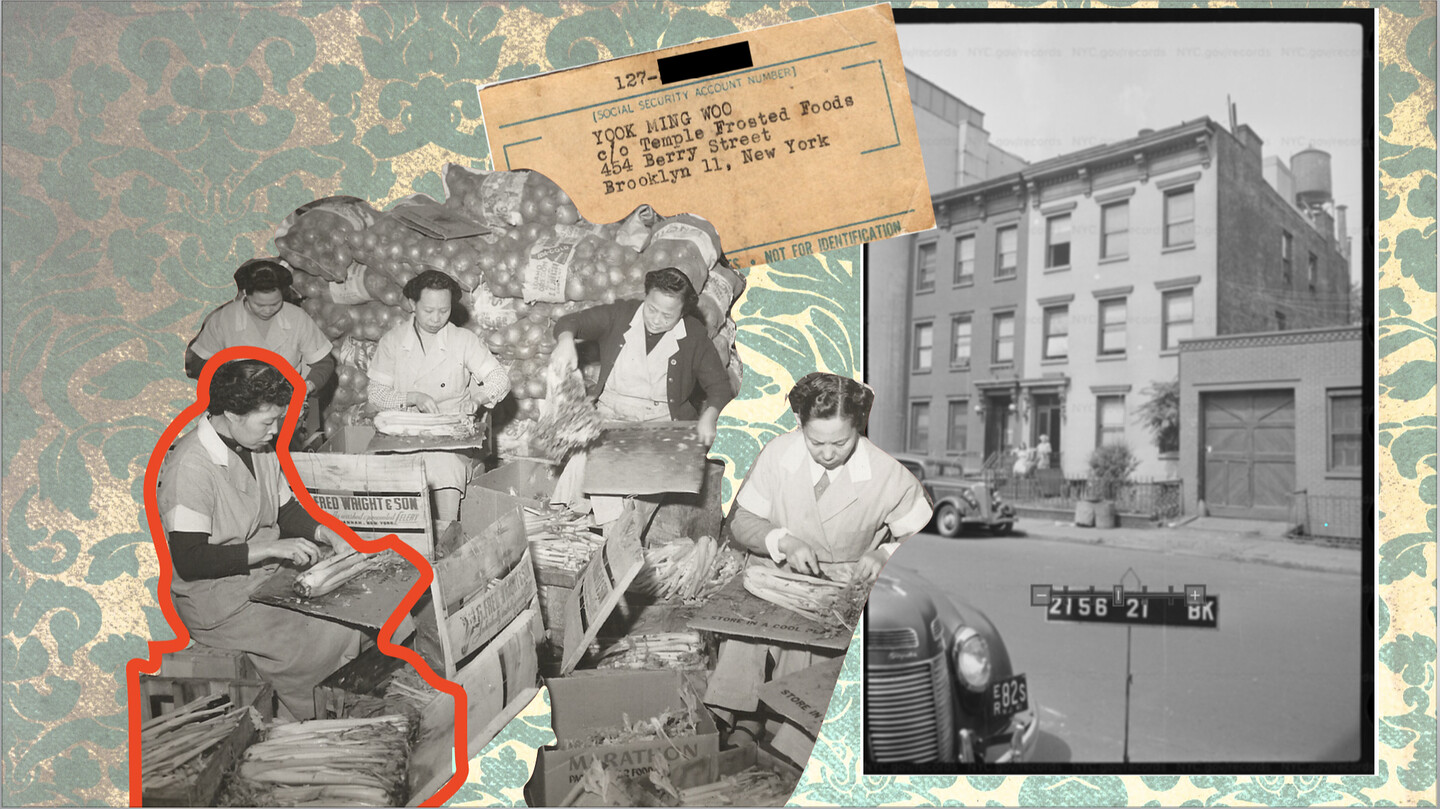

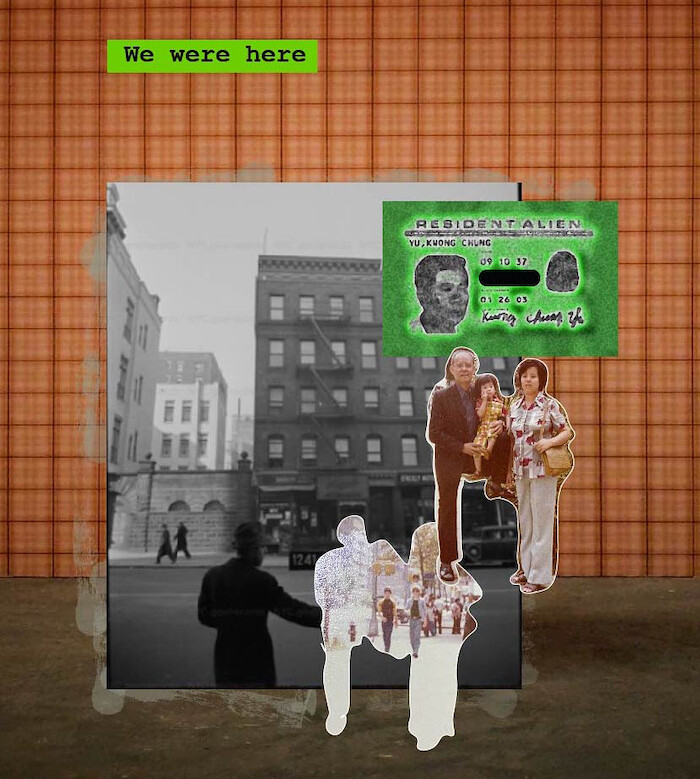

My paternal great-grandfather came to Reno, Nevada in the mid-to-late-1800s. My dad thinks that he might have operated a hand laundry business, or perhaps worked on the Central Pacific Railroads or in Silver Mines. Sadly, we don’t know the full story. During this time, angry white (supremacist) laborers destroyed small Chinatowns across the US that people like my great-grandfather helped build, chasing them away as they deemed them “a physical and moral threat.” Unable to build roots, my great-grandfather went back to China. Later, my grandfather, who was often called a “paper son,” came in the late 1920s by buying false papers that showed he had blood relatives already in the country. He owned and operated small hand laundries, one of the only industries that Chinese could work in because of rampant discrimination. Fast forward to 1972 when my parents arrived in the US to work long hours for low wages in garment factories until they retired.

The author’s grandma working at a food factory in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, circa the 1950s. Image by Betty Yu, 2021.

Fragments of My Block / Politics of Our Displacement

There is no direct Chinese translation for “Stop Gentrification.” The closest translation is 反对贵族化, or fǎnduì guìzú huà, which literally means “oppose aristocracy.” The term that is more widely understood and resonates with the Chinese-speaking community in the US is 驱赶, or qūgǎn, which means “displacement” or “eviction.” The politics of displacement and dispossession are deeply rooted in the fabric of US capitalism, imperialism, colonization, and modern-day state-sanctioned gentrification. One community member made the analogy between the white and wealthy folks who have been gentrifying Manhattan’s Chinatown over the past number of decades and the “gentry” of Hong Kong’s British colonial rule in the 1840s, when the city’s sense of culture and language was stripped away.

Since I was teenager growing up in New York City in the 1990s, I’ve been obsessed with documenting my neighborhood of Sunset Park, Brooklyn, which is now New York City’s largest Chinatown. I’m not sure exactly why I had this obsession, but I did, and still do. As early as I can remember, I was snapping photos of the neighborhood with a 35mm film camera. I photographed my family, friends, the kids on the block, and everyday moments. Later, when I went to NYU to study film, I shot hours and hours of footage of my family members. I eventually made a short film about how my mother, a garment worker, and my sister became fierce leaders in the fight against the sweatshop system in the 1990s. Looking back, I was probably trying to capture, preserve, and freeze those moments in time when my sense of home and sanctuary was never in question.

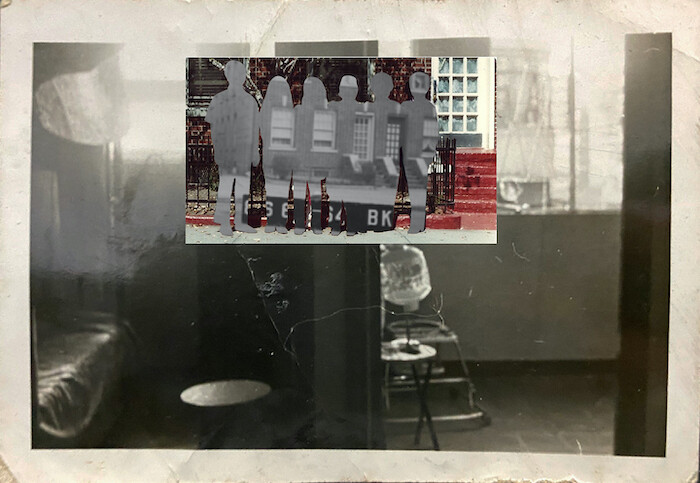

The author’s father’s US Alien card, juxtaposed with the author as a baby with her mother and grandpa in New York City. Image by Betty Yu, “We Were Here” series, 2020.

In the late 1970s, working immigrant families like mine were able to afford a house and achieve that slice of the “American Pie.” My family was part of the first wave of Cantonese speaking Chinese families to move into Sunset Park back in the late 1970s. I felt privileged to have grown up in the 1980s and 1990s in a neighborhood where I had friends from all backgrounds, but mainly Puerto Rican, Dominican, Chinese, and Northern European.

Since the 1950s, Latinx, and specifically Puerto Ricans, have been moving to Sunset Park. Today, the majority of immigrants (as opposed to Puerto Rican migrants) come from the Dominican Republic, Mexico, and other parts of Central America like Ecuador, Colombia, Peru, El Salvador, and Nicaragua. According to the 2010 census, almost half of the neighborhood is Latinx, and about forty percent is Chinese.

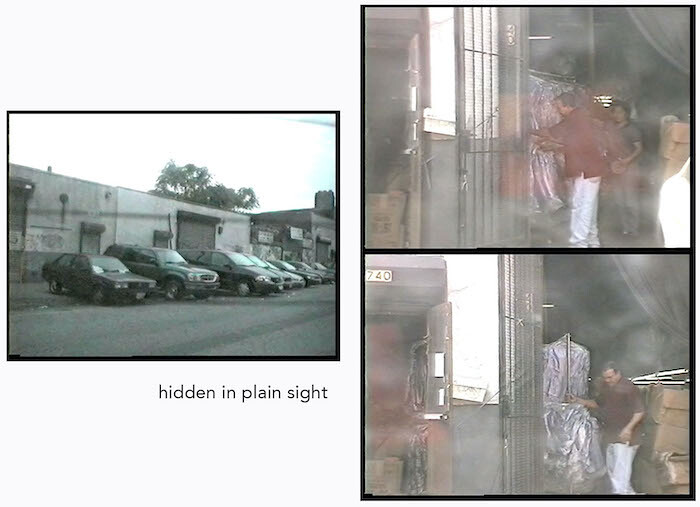

Betty Yu, hidden in plain sight (if you chose to look), 1999/2021. The author’s mother worked in these garment sweatshops, a few blocks from their house, in the 1990s.

Back in the late 1990s and early 2000s there were dozens of illegal garment factories operating out of warehouses and garages in the industrial parts of the neighborhood. Folks like my mother worked long hours for very low wages in these factories. However rents and the costs of living were still reasonable. Today, however, real estate developers aided by millions of dollars in government tax breaks threaten to displace thousands of working-class residents. Many parts of Sunset Park are still zoned for manufacturing, but developers have been trying to change zoning and land use laws so that developers can demolish existing low structures to build taller luxury housing, a real estate strategy known as “upzoning.”

In 2015, the $1 billion Industry City development project was unveiled for the Latinx area of Sunset Park. Industry City was planned to replace Bush Terminal, a manufacturing, shipping, and warehousing complex that was a site of employment for thousands of blue-collar US-born and immigrant laborers from the early 1900s up until the 1970s. The development project rebranded Industry City as an industrial waterfront for a “maker” innovation economy centered on manufactured hipster culture: “high” art, fashion, design, film and TV, tech startups, and specialized food sectors.

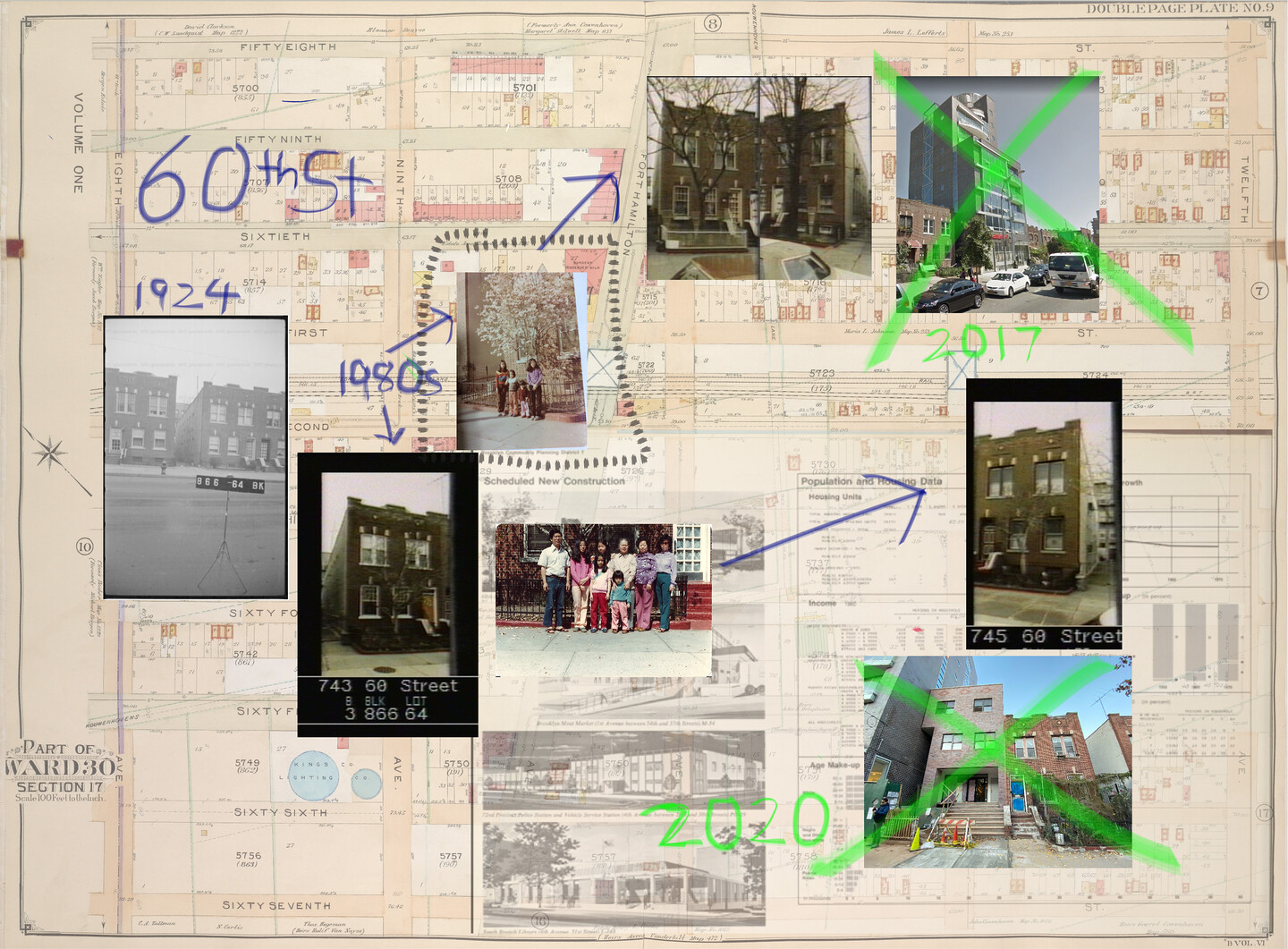

Changes on the author’s block and the towering condos surrounding her family’s house, layered over a map from 1905. Image by Betty Yu, 2020.

On the other side of Sunset Park, where I grew up, around 8th Avenue, overseas Chinese and domestic investors (from Flushing, Queens) have been buying up two-story residential homes and other properties and converting them into luxury condos, shopping centers, and other large capital ventures since 2012 with the help of banks in China. These new developments are not meant to serve the tens of thousands of working-class immigrants like my parents who live there, but instead are part of a systematic plan to replace current residents with higher income new inhabitants. At the same time, the Sunset Park Chinese population is expanding, as it absorbs working-class Chinese people who have displaced from Manhattan’s Chinatown. Meanwhile, long-time Chinese residents of Sunset Park are being subjected to rising rents and forced into smaller, more overcrowded living quarters in houses owned by unscrupulous landlords.

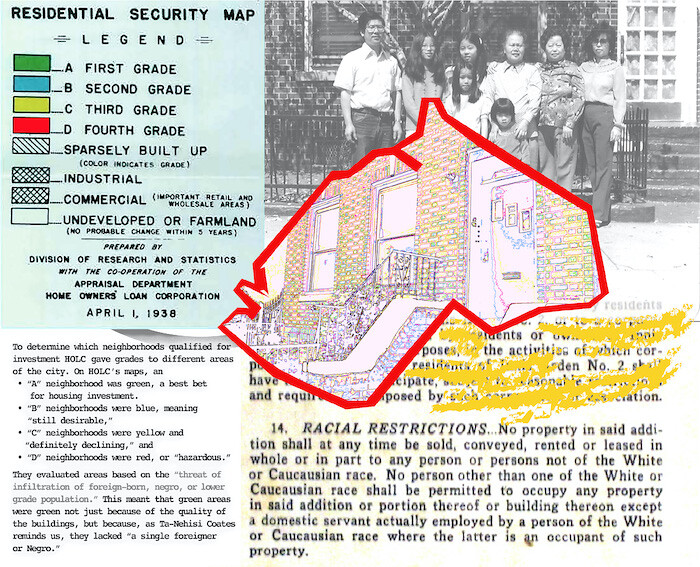

Redlined + Hazardous: the author’s Sunset Park home and family photo in front of their home in the early 1980s. Image by Betty Yu, 2021.

Back in the 1930s, Sunset Park was considered “undesirable” and redlined by the The Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), a government agency that, as Ta-Nehisi Coates explains, “pioneered the practice of redlining, selectively granting loans and insisting that any property it insured be covered by a restrictive covenant—a clause in the deed forbidding the sale of the property to anyone other than whites. Millions of dollars flowed from tax coffers into segregated white neighborhoods.”

To determine which neighborhoods qualified for investment, HOLC gave grades to different areas of the city. A Grade A neighborhood was marked green on their maps, signaling a best bet for housing investment. Grade B neighborhoods were marked blue, meaning “still desirable,” while Grade C neighborhoods were yellow, or “definitely declining,” and Grade D neighborhoods were red, or “hazardous.” HOLC evaluated areas based on the “threat of infiltration of foreign-born, negro, or lower grade population,” meaning that green areas were green not just because of the quality of the buildings, but because they lacked “a single foreigner or Negro.”

What has become known as Sunset Park was labeled Grade D. On top of this, after the war the neighborhood experienced white flight and de-industrialization, and by 1970, like much of New York City, it was in decay. In the 1960s, the entire neighborhood was officially given the name “Sunset Park” by being designated a federal poverty area and receiving federal funds. New immigrants, people of color and other working-class ethnic groups who stayed in the neighborhood throughout built it back up.

According to scholar and former Sunset Park resident Tarry Hum, “Brooklyn is the symbolic capital of New York City’s maker movement comprised of artisans and artists, designers, craftsmen, builders, innovators, and inventors. The adaptive reuse of the borough’s extensive industrial waterfront is integral to an innovation economy that derives social and economic value from place-based global branding.” Now, gentrifying forces want to capitalize on this at the expense of its people.

Notes on My Own Decolonization

My parents fled from poverty in Hong Kong when it was still a British colony, immigrated to the US, landed in Sunset Park Neighborhood, and purchased our house. The land beneath us, however, is not truly ours. It belongs to the Lenape first nation. The Brooklyn neighborhood now known as Sunset Park was home to the First People’s nation of the Lenape-Algonquian, of whom the Canarsee were an ethnic neighborhood. We cannot have a conversation about gentrification and displacement in Sunset Park today without first acknowledging the violence and genocide that was committed against its first inhabitants.

Betty Yu, Dis/Relocation—from Hong Kong to Brooklyn, 2021.

I grew up on 60th Street in the neighborhood currently known as Sunset Park. My parent’s house sits on stolen land. Yet I do not know the first occupiers of this land. I did not grow up knowing about the enslaved labor that built the city, that paved its streets. I did not grow up knowing about the Black Americans who were displaced from their homes during midcentury urban renewal, dispossessed from their land during the South’s Reconstruction era, or were redlined and disenfranchised from buying homes throughout the twentieth century.

In 1771, Brooklyn was made up of farmland and small villages. A third of its population consisted of enslaved people—the same proportion as in Virginia. Emancipation was gradual, taking place between 1799 and 1827. But in the late-eighteenth, early-nineteenth century, Brooklyn was the slaveholding capital of New York State. On average, sixty percent of white families living in Brooklyn were slaveholders. In the town of Flatbush, it was as high as seventy-four percent. Brooklyn’s slaveholding percentages surpassed those of South Carolina.

In the 1930s, during a Works Progress Administration’s project in Sunset Park, “relics were unearthed at the old water pond by the WPA park crews during the construction of the new pool.” What they found was the former village site of the Nyack Indians. Furthermore, according to a 1911 Brooklyn Eagle article, relics, bones, and graves were also found at Owl’s Head Park, a hillock that forms the highest point of the estate also known as Indian Mound. Congressional funds were set aside at the time to build a monument to commemorate the site, but of course, it never materialized.

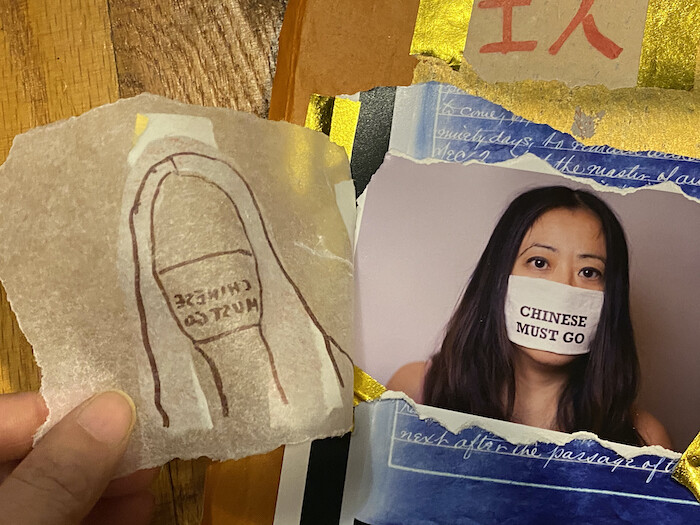

The author wearing a mask with the printed text “Chinese Must Go,” a popular slogan during the rise of anti-Asian violence in the US in the 1870s. Today, 150 years later, the author contemplates a similar climate. Image by Betty Yu, 2020.

Standing within this history, we should ask how the fight for abolition of prisons, reparations, and decolonization is part of our own? We should ask what it means to decolonize, within our own practices, within our own social movements? We should ask how we build genuine solidarity, one that acknowledges that our liberation is inextricably tied to one another?

From 1846 to 1853, the wealthy white landowner and abolitionist Gerrit Smith donated forty-to-sixty-acre lots to 3,000 African American men in upstate New York, in the Adirondack mountains. Establishing a socialist utopian community called Timbuctoo on 120,000 acres of his own land, Smith responded to New York’s failure to secure black citizenship and voting rights by creating a community of black voters. More recently, in 2020, the Portland arts organization Yale Union transferred its land and building to the Native Arts and Cultures Foundation (NACF), a Native-led national organization that advances Indigenous arts and artists.

Acts of Reimagining

Many folks of color, low-income workers, and those organizing on the frontlines don’t have the luxury of time to intellectualize or reimagine a new kind of society when they are fighting like hell against our current one. Frameworks oriented around “futurisms,” “re-imagining,” and “re-envisioning” can feel removed from people’s everyday lived material conditions. With the twin pandemics of white supremacy and COVID-19, 2020 and now 2021 has been dystopic enough for many to think outside of the box, to imagine a different kind of society that is more just—that upholds racial, economic justice, immigration, healthcare, housing, and environmental justice. Radical imagination is critical at this historic juncture, because when we give ourselves permission to dream, to re-imagine and unleash our visions of emancipatory futures, we make strides toward realizing it.

The power of social imaginaries and cultural production tools lies in its ability to engage people who are directly impacted by these injustices. In 2015, when I helped co-found the Chinatown Art Brigade (CAB), an Asian-American artist collective that centers art and culture in social justice work, we understood the process of collective, radical reimagination as a fundamental way to support community-led efforts around issues of gentrification and displacement. Early on, working with CAAAV’s Chinatown Tenants Union, we set up workshops that included collecting oral histories, story circles, resident-led walks, photography, audio recordings, community counter mapping, and video documentation. “Here to Stay,” a series of large-scale outdoor projections of local stories of resilience and resistance, were co-created with the Chinatown immigrant tenants and residents.

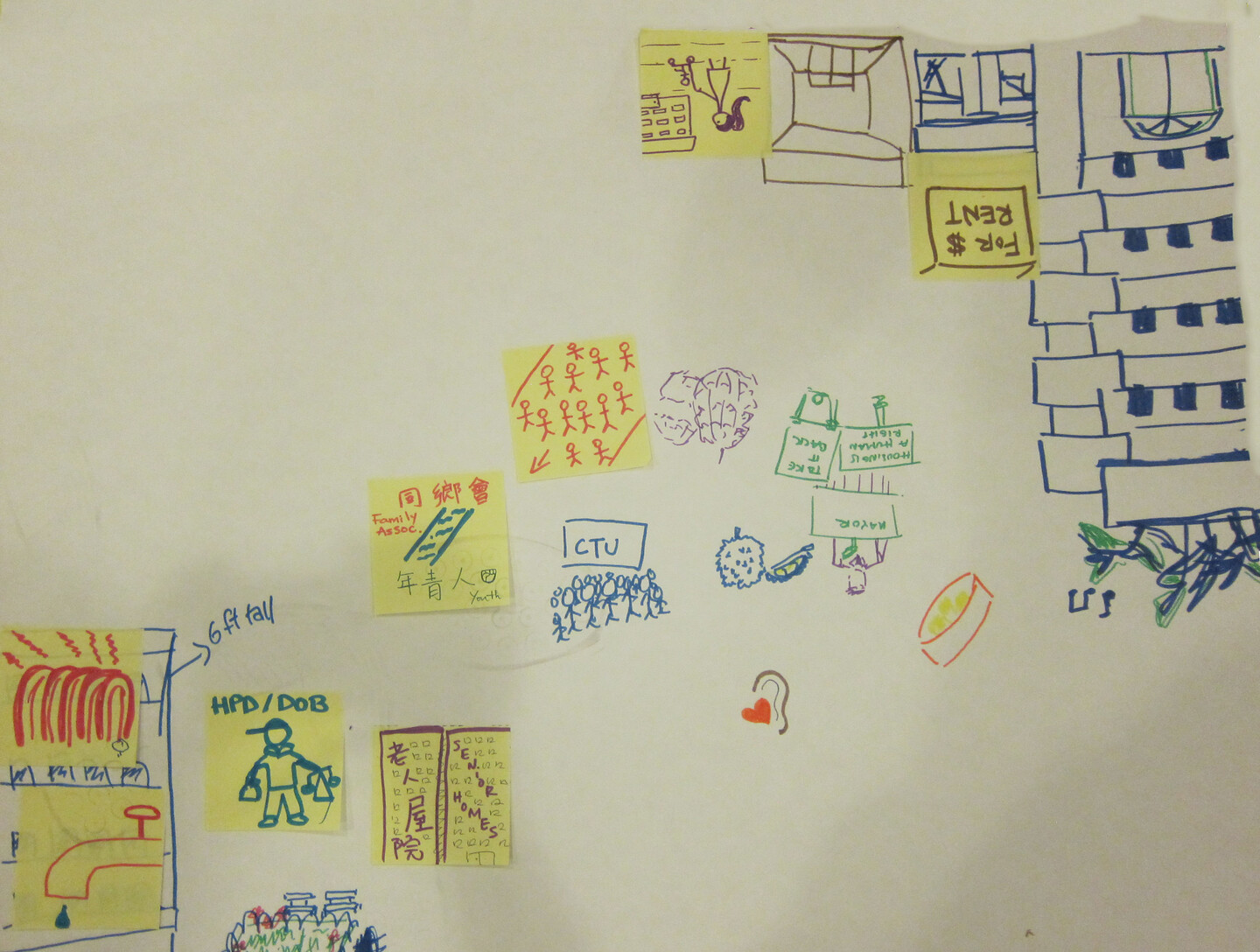

Chinatown Art Brigade, Imagining a Future Chinatown, 2016. Community members envision housing justice through drawings and maps.

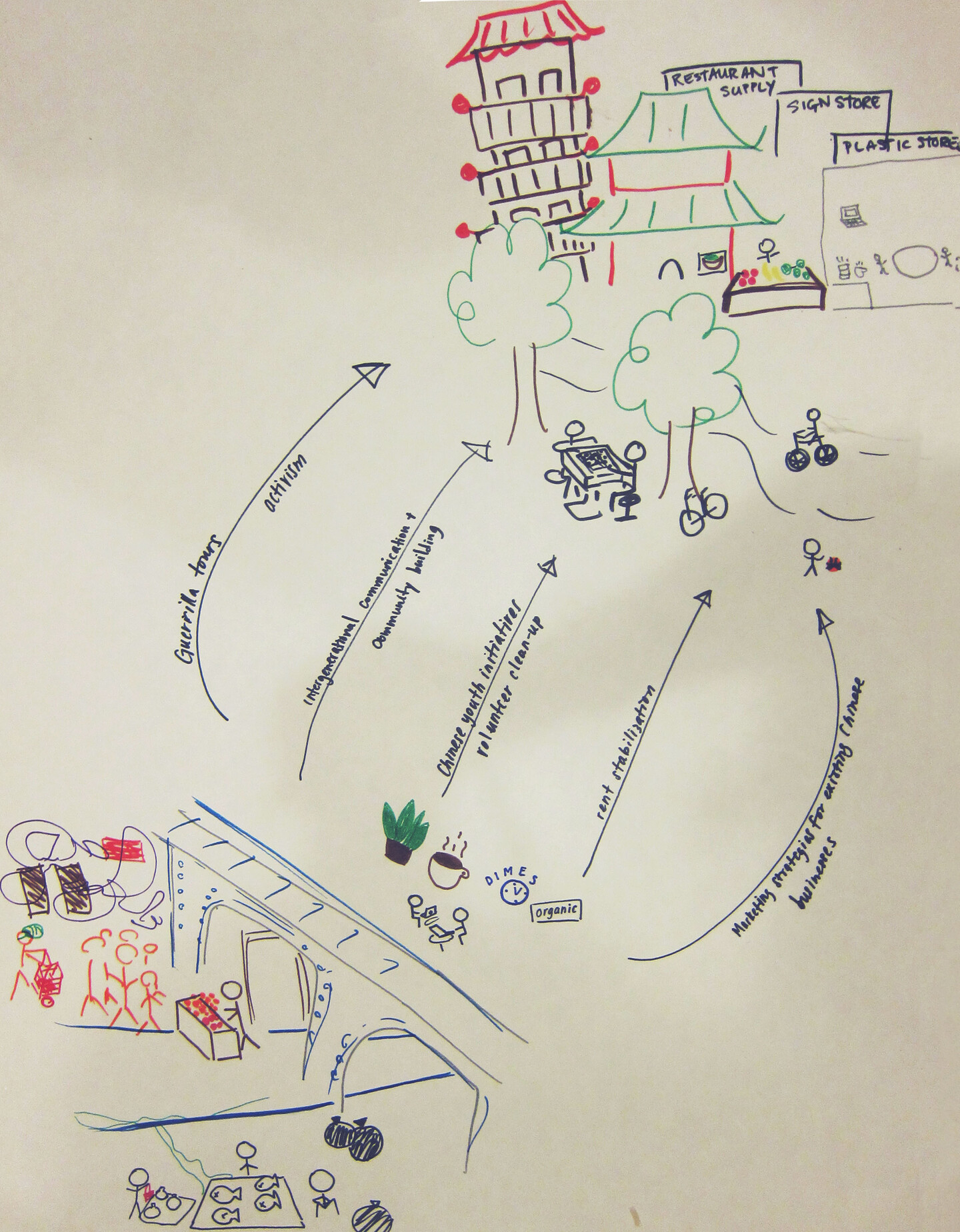

Chinatown Art Brigade, Imagining a Future Chinatown, 2016.

Chinatown Art Brigade, Imagining a Future Chinatown, 2016.

In one workshop, titled “Imagining Housing Justice,” we asked folks to draw out the kind of future they were fighting for in Chinatown and the Lower East Side. Instead of responding and just being reactive to current conditions in Chinatown, we encouraged community participants to imagine housing justice without limitations. They were asked to draw “our current conditions/state of our reality,” “the community’s future,” and “the transition and pathways” to get from the current situation to the ideal future. Most of the workshop participants commented that “imagining a future of housing justice” was difficult, but as we started to brainstorm, people started to draw and write their hopes for real affordable housing, community art centers, more green spaces, public parks, free healthcare, free daycare, community policing, job training hubs. We then had a thought-provoking discussion about the dedicated organizing work, coalition building, and a radically different society we need in place for this to be a reality.

This kind of “cultural placekeeping” work, unlike “creative placemaking” efforts that are often dictated by artwashing and predatory real estate interests, is grounded and led by people most directly impacted by displacement. “Placekeeping” celebrates and honors the resilience of people, place, and culture and most importantly recognizes the active care and maintenance of its people who live and work there. It is not just about preserving buildings or cultural memories associated with a place, but rather the ability for local people to stay in their homes and maintain their way of life as they choose.

Still from Chinatown Art Brigade’s “Here to Stay” projection series, 2016. Photograph by Louis Chan.

In my community-based, multimedia interactive mapping project “(Dis)Placed in Sunset Park,” it was important to not only celebrate our community’s resistance to displacement, but to also examine and interrogate the shifting borders of Sunset Park as it relates to the changing boundaries for plans created by real estate speculators and developers. These developers, sanctioned by city officials, have co-opted the tools of “reimagining” for their own profit-driven and political gain. They claim that gentrification is “inevitable” and a part of “natural evolution.” They assert that these re-envisioned urban plans need new (higher-income) residents, new maps, new borders, and new names.

A work-in-progress version of (Dis)Placed in Sunset Park exhibited at Case Gallery at Skidmore College, 2017. Photograph by Betty Yu.

We know that borders are a social construct. We also know that modern-day maps have been a tool used by colonizers to legitimize stolen land and property ownership. How, then, can we decolonize the power and authority of borders in maps and reassert our own placekeeping narratives? It’s only in the last decade that the city and real estate developers have renamed parts of Sunset Park to “Greenwood Heights” and “South Slope.” “(Dis)Placed in Sunset Park” focuses on “counter-mapping” strategies that acknowledge the oppressive role of maps and borders while also understanding the need to appropriate its techniques to lift up underrepresented people, uncover untold histories, and bring into focus places not recognized by dominant narratives.

Despite being socially distanced today, we are seeing new social formations, new ways of organizing, new practices that blur the lines of art and activism. We are staring ahead at a greed-caused climate catastrophe in a possible post-Anthropocene, with AI-powered racialized capitalism creating greater division, competition, and surveillance. In the midst of so much injustice and tragedy, cultural change is inextricably tied to political and societal transformation. With our backs up against the wall, humanity calls us to rise up, to dismantle our current structures, and reimagine a different, liberated future.

×

Survivance is a collaboration between the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and e-flux Architecture.

Betty Yu is a multimedia artist, photographer, filmmaker, and activist born and raised in New York City to Chinese immigrant parents. She is a co-founder of Chinatown Art Brigade, a cultural collective using art to advance anti-gentrification organizing, and also teaches video, social practice, art, and activism at Pratt Institute, Hunter College, and The New School.