Carla Rathway could hear her youngest son’s frustration from the other room. She knew the clamor meant the internet was acting up again and keeping 12-year-old Preston from his school work. It happened all the time.

“He’s like, ‘Oh my gosh,’ when it’s buffering or locking him out,” Rathway said, adding she also overhears him saying, “‘I hate this internet.'”

Like scores of Pennsylvania students, Preston, a seventh grader at Belle Vernon Area School District in Westmoreland County, and his brother, 15-year-old tenth-grader Dylan, were in their second month of online learning this October. But the brothers were doing it all without a reliable high-speed internet connection at home, where they live across the county line in Fayette County.

In place of one, Preston and Dylan relied on an ad hoc network of erratic mobile hotspots and visits to relatives in order to complete their assignments.

Makeshift solutions, like these, exist all around them.

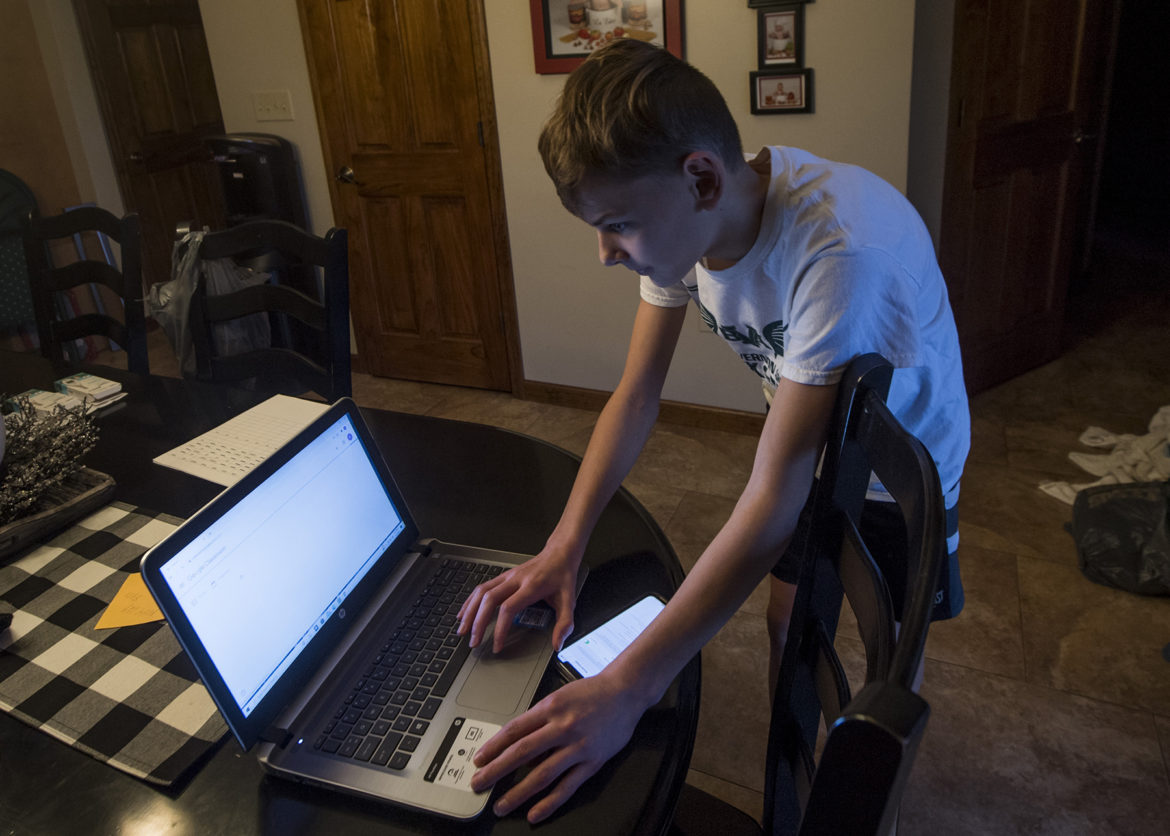

Preston Rathway, 12, of Fayette County, works on schoolwork using a mobile phone hotspot for internet access while at home on Jan. 4, 2021. (Photo by Nate Smallwood)

Elsewhere in Fayette County, public school students are going to emergency facilities such as firehouses and churches to access the internet. And several districts are experimenting with broadcasting classes on TV at an appointed time — instead of having students log online.

In neighboring Washington County, one school sent out vans with mobile hotspots meant to help extend the area’s Wi-Fi connections. Farther north, districts in Beaver and Butler counties put access points on school buildings so that families can park in the school lots to use the internet. And across the region, small businesses are opening up their internet access to students.

Internet service providers such as Comcast — one of the largest home providers in the country — say their coverage areas are constantly and naturally expanding. But experts point to the literal race underway to equip young learners in Pennsylvania and say that none of this is happening or working quickly enough.

In 2013, Pennsylvania awarded millions of dollars in tax credits to private companies to improve broadband internet in rural areas — without requiring them to actually invest there. Last fall, the state legislature created a new program meant to replace it, offering similar incentives to the telecom industry. Advocates are skeptical that it’ll close the divide between those who have high-speed internet access and those who don’t.

Closer to Pittsburgh, where internet service providers have made coverage more reliable but not always affordable, students are taking advantage of the providers’ assistance programs, relying on deeply discounted access to the resource that, as the pandemic rages on, connects them to their classmates and teachers.

Similar or identical stories can be found in rural and urban districts across the commonwealth.

While the underlying access gaps aren’t new, this pandemic might prove to be a tipping point in how we view the service: privilege vs. utility.

Related stories

Until then, solutions remain piecemeal and almost wholly reliant on private sector whims or the triage efforts of startups and nonprofits.

“Everybody says we’ll look into it,” Dylan’s dad, Brian, said about their bids for assistance. “That’s what everybody says.”

A desperate rush as schools spend millions for quick fix

When Gov. Tom Wolf ordered all Pennsylvania schools closed for in-person learning in March, districts pivoted quickly to online-only models with varying degrees of success and crisis-measured expectations. The governor’s order was extended for the duration of the 2019-2020 school year in April, but reopening plans for the following school year — the one we’re in now — were largely left up to local officials. Some chose a wait-and-see approach.

When the summer brought no miracles — no vaccine, no real reduction in new COVID-19 cases — those districts joined others nationwide in scrambling to secure the technology students needed for a post-summer continuation of online learning.

This included devices, like tablets and laptops, needed to use online learning tools. It also meant technology that brings the internet into the home, namely portable beacons called hotspots that rely on cellular networks, which are used by those who aren’t served by commercial internet providers. For those who were, the districts sought ways to offer a discounted service.

To tell the full story of COVID-19’s effect on our community health, safety and security, the members of the Pittsburgh Media Partnership are working together. And we need your help, too. Help contribute to the story: What has school been like for you or your family over the past year?

Many of the 157 public schools in the seven-county region that makes up the Pittsburgh metropolitan area were able to cover the costs of these devices from their operating budgets or with federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act money, according to a phone survey conducted late this fall by the members of the Pittsburgh Media Partnership — despite issues related to the equity in the disbursement of that aid. But even for those who knew the check was in the mail, cash flow became its own crisis.

For example, Pennsylvania received $104 million from the federal government to expand internet access for K-12 and college students, but two-thirds of that pot still hadn’t been distributed by the state as of August, with just weeks left before the start of the school year. The Pennsylvania Department of Education has since said the entire pot has been allocated, with some contracts still being finalized.

Faced with those delays and with a second round of federal relief funding a distant prospect at best, school administrators said they needed all the help they could get.

Districts like Pittsburgh Public Schools, Pennsylvania’s second-largest district, held a community fundraiser to help bankroll purchases of online learning tools and families’ monthly fees for internet service.

Nonprofits such as the Jerome Bettis the Bus Stops Here Foundation and Best of the Batch Foundation stepped in to help other districts. Private companies also made donations. U.S. Steel, for one, donated $25,000 each to the McKeesport Area School District and Clairton City School District, and undisclosed amounts in South Allegheny and Woodland Hills, a spokesperson confirmed.

The rush to secure funding overlapped with a rush to spend it, and the sudden run on electronics that followed caused a nationwide shortage, the same blamed for contributing to early distribution delays here and across the country.

Desperate school officials unable to get the tech they needed through their vetted suppliers cold-called big box retailers, like Staples and Best Buy, to comb through their inventory.

Sto-Rox curriculum director, Michael Amick, poses for a portrait inside of a classroom at the Sto-Rox Primary Center on Dec. 18, 2020. (Photo by Nate Smallwood)

“We were really stressed about three weeks before school started,” said Michael Amick, the curriculum director for The Sto-Rox School District in McKees Rocks, a borough on the western end of Allegheny County, just outside of Pittsburgh. “We just lucked out because Staples had an order of 500 devices canceled — we were able to get them just in time.”

More than half of Sto-Rox’s 1,432 students didn’t have a computer at home at the start of the pandemic. Seventeen-year-old Arielle Murrell of McKees Rocks, a twelfth grader in the district, relied on her phone to complete assignments on websites not at all designed for that. Sixteen-year-old Tam’Bryah Burrell, a Sto-Rox tenth grader also in McKees Rocks, shared a laptop with her aunt during the initial pivot to online learning in March.

Sakinah Shaahid – who, through her work for education non-profit Communities in Schools, checks in almost daily with Arielle, Tam’Bryah and about 50 other students at Sto-Rox and neighboring districts – said many students without adequate technology missed out on a vital chunk of their education between March and September.

“When the district made it so that every child passed, you saw a lot of students who probably didn’t have access to technology, they just didn’t do any work because they were passing anyway,” she said.

“We had plenty of devices. The biggest obstacle was the families that didn’t have the internet.”

Amick said that after that rocky spring, the district was able to make sure every student and teacher had access to a Chromebook when the school reopened in the fall. That is no small feat in a district where one-quarter of families live below the poverty line and where budgets are so tight the school once famously ran out of paper.

“This really changes everything for us,” Amick said, at the time. “Now I feel like our students can compete, they can connect with the broader innovation in the region.”

In nearby Coraopolis, a 15-minute drive from the Sto-Rox School District, the Cornell School District, where 99.5 percent of its students qualify for free or reduced lunches, also found a way to deliver devices to all of its 675 K-12 students.

But the school officials found that getting the hardware distributed was just the beginning of a solution to the challenges they faced with the move to online classrooms.

“We had plenty of devices,” Cornell Superintendent Aaron Thomas explained. “The biggest obstacle was the families that didn’t have the internet.”

Frustrated families at mercy of industry

A March survey of Cornell School District families found about 10 percent of its families had no internet connection at home. More reported connections that simply weren’t reliable enough for the demands of online learning.

At Sto-Rox, it was roughly the same, school officials estimated. Tam’Bryah now has a district-issued device but sometimes she still toggles between it and her aunt’s laptop.

Sixteen-year-old Tam’Bryah Burrell, a Sto-Rox tenth grader, shared a laptop with her aunt during the initial pivot to online learning in March. (Courtesy photo)

“It’s very challenging,” Tam’Bryah said of the impact on her school work, adding that teachers have also struggled as instructors-turned-IT support. “Some of them just send emails saying do this or do that (to fix a tech issue), but that don’t help.”

Fifty minutes south, in Washington Township in Fayette County, Robinette Vitez’s son, Dalton, watches the weather to see if his connection, through HughesNet’s satellite service, is likely to work.

“I can tell you if it’s clear out, he can get online,” Vitez said. “If there is a cloud in the sky, he gets bumped off.”

Vitez said Dalton typically gets good grades but was falling behind this year. He’s having the biggest issue in Spanish class, she said. Videos and digital feeds for the class constantly lag or freeze when Dalton is talking to his teacher or classmates. He also has trouble hearing what everyone else is saying.

“I’ve actually reached out to the school and talked with the guidance counselor trying to figure out what we can do because, I mean, that’s out of his control,” Vitez said. “I’m not going to accept an F or D from an A-B student. That’s just not acceptable to me. It’s not the kid’s fault.”

According to an April 2020 U.S. Census Bureau survey, some 3.7 million U.S. households have had internet available sometimes, rarely, or never for online learning in this pandemic — with rural students, students from lower-income families, and students of color disproportionately affected.

For those who technically have access to what the Federal Communications Commission refers to as “broadband” internet (access that is “always on” and faster than a dial-up connection), there is significant disparity in the quality of the connections based on where you live and its market appeal to the (mostly) for-profit companies who lay the nation’s infrastructure for internet services.

“Until this (pandemic) happened, people just kind of sucked it up. But as time goes on, everything has become internet based, and right now, everything is online.”

Physical cables connected to houses — telephone, cable or fiber optic lines — provide more reliable coverage than wireless broadband technologies that rely on radio or cellular signals bouncing off physical towers nearby. But even the physical connections vary in how fast they can connect you: Cable lines are better than telephone line connections, and fiber optic cables, built specifically to deliver high-speed internet, are the fastest.

Tam’Bryah and her aunt, in the denser, more urban environment of Allegheny County, have options — depending on what they’re willing to pay. Costs to connect a high-speed internet connection, when available, can range from about $40 per month to more than $70 per month.

After distributing hardware, most districts are relying on internet service providers’ assistance programs to help families struggling with the ongoing expense of the internet connection, according to the Pittsburgh Media Partnership’s survey.

A few were able to help pay for the expense directly. After Pittsburgh Public Schools, for example, found that more than 1,500 of the district’s 23,000 students — roughly 6.5 percent — lacked internet access, it distributed access codes for Comcast’s most basic home WI-FI service, which were purchased with a local nonprofit’s $100,000 donation.

The urban environment surrounding most PPS students also provide options for free Wi-Fi access, too, through libraries within walking distance, and neighbors and businesses who share their access.

“I think that most of the kids are pretty good with connectivity,” said Sean Means, a teacher at Pittsburgh Westinghouse Academy 6-12.

They seem to be, he said, “in a much better place than we were at any point in the history as far as being able to get online.”

But students in the region’s more rural areas are being stranded on the berm of the information superhighway and struggling to keep up.

Preston Rathway, 12, of Fayette County, uses a mobile phone hotspot to access school material on his laptop while at home on Jan. 4, 2021. (Photo by Nate Smallwood)

In Fayette County, the Vitezes’ and their classmates, Preston and Dylan Rathway, are two of the roughly 30 Belle Vernon School District families without high-speed internet access at home, school officials report. The resulting tech hurdles — dropped remote learning calls, out-of-sync audio, endless buffering — were so bad that Preston demanded to go back to in-person classes, his mother, Carla said, which he did two days a week. But the district’s COVID-19 test positivity rate soon tripled, eventually reaching 47 percent, and he was soon back at home.

They are tantalizingly close to better internet access.

“If you climb that hill behind our house,” Brian Rathway said, pointing to a grassy knoll, “and back down the other side, they have Atlantic Broadband.”

But extending that line requires building new infrastructure, and that can carry a shocking price tag.

“The estimate came back for me that I was going to have to pay $90,000 for them to run the line so I can have high-speed internet,” relative and nearby neighbor Larissa Rathway explained, even with households a quarter-mile away already tapped in.

Another family was given a $30,000 quote, Washington Township Supervisor Jan Amoroso said.

“Until this (pandemic) happened, people just kind of sucked it up,” Amoroso said. “But as time goes on, everything has become internet based, and right now, everything is online.”

High-speed questions: is it a utility or a privilege?

If there is a silver lining to this educational crisis, it’s that forced acknowledgement that the internet is no longer a luxury — particularly for American students.

“It’s like that time-travel book [by H.G. Wells],” says Adam Longwill of Meta Mesh Wireless Communities, a Pittsburgh-based nonprofit that uses novel means to fill internet service gaps here. “There’s the above-ground people and the underground people. And they are the same, like, they evolved from the same humans. But they’re just totally and completely incompatible with each other.”

The metaphor continued: “We are creating a society of the connected and the disconnected that are going to be so far apart if we continue to let this happen, I don’t know how we’ll ever get back together.”

Gov. Tom Wolf, in an attempt to address this digital divide, signed into law in November the Unserved High-Speed Broadband Funding Program Act.

State Sen. Wayne Langerholc Jr., a Cambria County Republican and primary sponsor of the bill, said the legislation was first conceived in 2017 and regained its momentum this summer after a lengthy stay in committee.

“We are creating a society of the connected and the disconnected that are going to be so far apart if we continue to let this happen, I don’t know how we’ll ever get back together.”

The act created a $5 million grant program to incentivize private-sector companies to add high-speed internet in places where sparse populations and lower rates of return have always been a disincentive.

For the purposes of the grant program, the law also updates the definition of which areas of the commonwealth are being served by high-speed internet. The law uses the FCC’s minimums, rather than the ones set by Pennsylvania’s Public Utility Code, which relies on decades-old metrics and which is at least part of the reason why families from the Belle Vernon School District in Westmoreland County to the Sto-Rox School District in Allegheny County struggle to stay connected.

The FCC’s higher watermark sets basic service at 3 to 8 megabits per second (mbps) for both downloads and uploads and high-speed service at more than 25 mbps. To put that in context, an average-sized cellphone photo would take about 8 seconds to download at 3 mbps and exponentially less time from there. Those speeds are less adequate when considering the more demanding activities required for online learning, especially when a household has more than one device running at a time. By the FCC’s own standard, basic service is just barely good enough for the rigors of video conferences and calls.

But while the new grant program corrects for the commonwealth’s low standard, advocates are skeptical it will make a difference. Most underserved areas of the state won’t be eligible for the support promised because they will be officially labeled as “served” when in fact they are not, said Sascha Meinrath, a Penn State professor in telecommunications who led a recent study testing broadband speeds access.

The study, conducted in 2018 and released in 2019 by the bipartisan Center for Rural Pennsylvania, found “a systematic and growing overstatement of broadband service availability in rural communities” by internet service providers, noting discrepancies between the self-reported internet provider data collected by the FCC and tests run by independent researchers.

Kyle Kopko, the center’s director, estimates 253,000 rural households in Pennsylvania — 15 percent of the state’s rural total — still have no internet at all.

Dalton Vitez, 15, of Fayette County, works on schoolwork while at home on Jan. 4, 2021. Photo by Nate Smallwood)

Meinrath said the bill is weak in other ways. It doesn’t allow municipal entities — like Washington Township in Fayette County — to take advantage of the grant program on their own.

There’s also nothing restricting data caps, throttling or other artificial limitations on speed and bandwidth imposed by providers. (Meinrath estimates only five to 10 percent of Pennsylvanian households can currently support three Zoom calls at the same time — not an uncommon occurrence these days with students and parents all working from home.)

Langerholc said he’s open to amending the bill as needed to “meet needs maybe we didn’t foresee at the time.”

“No law is perfect,” he added, “and if we’re going to legislate based on naysayers, that’s not gonna work … And this comes at a time when it is sorely needed.”

Robert Grove, a spokesperson for Comcast/Xfinity, said the pandemic has highlighted a growing need for the service.

Between March and May, the company reported a 32 percent increase in upstream traffic — meaning the amount of data being sent from computers or networks in the form of outgoing emails, file uploads, and more. Comcast also reported an 11 percent increase in downstream traffic — meaning data received by a computer or network through incoming emails, file downloads, webpage visits, and more.

Grove declined comment on the criticism of the legislation.

Schools race to close gaps themselves

Meanwhile, school districts across the region head into the second half of the school year with their own solutions.

In Butler County, the Karns City Area School District added external access points to the exterior of school buildings so that families can access the internet from the parking lot. They also added one to the press box of the high school football stadium so that, on nice days, students can sit on the bleachers and use the internet, said Foster Crawford, the school’s director of technology.

“We live in a very poorly-run internet area,” Crawford said. “We are lucky if half of our students are able to get broadband access. Most are getting DSL. It’s pretty rough.”

In Washington County, McGuffey School District officials equipped school vans and other vehicles with mobile hotspots, parking them in church and public parking lots closer to where students live. “Our parents/students can sign up for access and then we will arrange to drive the units out to the requested areas of the district at specific times,” said Michael S. Wilson, the school’s director of technology and transportation, in an email.

McGuffey, the Avella Area School District and, in neighboring Fayette County, the Brownsville Area School District, are all also experimenting with broadcasting classes through Pennsylvania PBS, said Brownsville assistant superintendent Bethany Hutson.

“From our local surveys of families this past summer, 39 percent of families reported that they did not have internet access to support remote learning,” Hutson said.

Troy Pellick, 18, and Alexa Pellick, 14, of Grindstone, work on schoolwork using the internet at the Grindstone Volunteer Fire Department Social Hall on Jan. 4, 2021. (Photo by Nate Smallwood)

School officials around the region are also coordinating with church halls and fire halls to open their doors — and internet connections — for students. Rich Lenk, the fire chief for the Grindstone Volunteer Fire Department in Fayette County, said there are sometimes as many as 15 or 20 students at a time relying on the department’s internet, either from the parking lot or from inside the fire hall.

And two districts, the New Kensington-Arnold School District in Westmoreland County and the Cornell School District in Allegheny County, are doing what once seemed unthinkable: They are building their own internet network.

The pilot project — spearheaded by Meta Mesh Wireless Communities and partners at Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Pittsburgh — takes internet bandwidth donated by the Keystone Initiative for Network Based Education and Research, a nonprofit internet service provider, and pools it into a shareable and public stream, bringing free internet to students and families that wouldn’t otherwise have it. The project is being jointly paid for by CMU and the Hopper-Dean Foundation.

When all is said and done, the free signal will stretch among a trio of radios — one atop the Cathedral of Learning in Oakland, one atop a water tower in Coraopolis, and one on Neville Island in the headwaters of the Ohio River — reaching underserved communities like Coraopolis, Homewood, and New Kensington.

“It was really important to us that we not make band-aid solutions going into this,” said Ashley Patton, a computer science specialist at CMU who was approached by Cornell’s director of technology and instructional innovation, Kris Hupp, last year.

With help from Patton and her colleague, Maggie Hannan, a learning scientist and engagement specialist at CMU, Hupp was introduced to Longwill, Meta Mesh’s executive director, and a plan was quickly formed.

Registration is currently open for residents of Coraopolis, Homewood, and New Kensington to join the network. Families with students will be prioritized, but all who need it are welcome to apply.

The service itself is expected to be up and running by the end of the 2020-2021 school year, with the goal of expanding to more western Pa. communities beyond the first year.

“We wanted to provide something that was durable and a better option than the stop-gap solutions,” Patton said.

This story was produced as part of a collaborative reporting project by the Pittsburgh Media Partnership. Learn more about our partners in the collaborative and sign up for the partnership’s newsletter to get weekly summaries of the region’s most important stories.

TyLisa C. Johnson of PublicSource, Jordan Woman of the Brown and White at Lehigh University, and Zoey Angelucci and Logan Garvey, both of Point Park University, contributed reporting to this project.