In Yangon, Myanmar, displays of conspicuous wealth adorn high-end real estate developments located at strategic downtown intersections and clustered around the city’s famous Kandawgyi and Inya lakes. While there is nothing exceptional about these buildings—enclosed atriums, shopping malls, tinted glass office towers, hotels, and condominiums—these developments contrast sharply with the decaying colonial infrastructure, congested roads, and bustling open street markets around them. In 2018 and 2019 we spent time in two of these shopping malls, paying $6.00 for barista-made cappuccinos, perusing the opulent interior décor replete with ambient lighting, fake ornamental tropical plants, and marble-lined fountains while circulating around atriums lined with international brands like Armani, Coach, Hugo Boss, and Versace. While the malls were not full, there was clearly a market for their products among wealthy Burmese nationals. The story of these buildings—who financed them, who built them, who frequented them, and how they related to the wider political economy of Myanmar—is the story of the murky dealings of the governing State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) of the 1990s, the ceasefires it negotiated with insurgent groups along the Chinese border, and to the jade mines in the restricted northern state of Kachin.

Crony Capitalism

After the 1988 uprising in Myanmar, the military junta reinvented itself as the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) with a commitment to negotiating a new constitution as a precursor to democratic elections, to liberalizing and privatizing the economy, and to transitioning from socialism to a market-oriented economy. The military used the liberalization process to its advantage, expanding its industrial base and extending its reach into the economy. It established two large conglomerates whose majority shareholders were current or former military officers: Myanmar Economic Holding Limited (MEHL) and Myanmar Economic Corporation (MEC), both of which became closely linked to the extractive industries and through which it continues to launder money. The 1990s also gave rise to a particular form of crony capitalism. In Myanmar, crony capitalism favors certain individuals with close connections to the military and who were selected by the SLORC as “national entrepreneurs” to benefit from the transfer of state assets.

Intersection of Sule Pagoda and Anawrahta Roads, Yangon, 2019. Photograph by Lindsay Bremner.

Ceasefire Capitalism

While the SLORC was selling off the state’s assets to itself and its cronies, it was negotiating ceasefires with insurgent groups along the border with China, where some of Myanmar’s most profitable resources—Burmese teak, jade, and drugs—are found or produced. Historically, these highland areas remained peripheral to the state apparatus and semi-independent from lowland centers of power. Struggles between distinct ethnic groups who inhabit the remote uplands and the Burmese state go back for centuries, but were exacerbated during the second world war when the British recruited civilians from upland Kachin, Karen, and Shan groups to fight against the Japanese, while the fledgling Burmese Independence Army was trained by and allied itself with the Japanese. Conflicts were compounded in 1949 when Chiang Kai-shek’s retreating army, backed by the CIA and Thailand, marched into Burma from Yunnan, the Chinese province neighboring Myanmar. This resulted a complex web of post-independence conflicts between the Burmese army, Chinese nationalists, and ethnic militias fighting for autonomy or independence or for control over opium and heroin cartels.

At the same time, the militias of the Burmese Communist Party were fighting for a People’s Republic of Burma backed by China. Then came reform in China under Deng Xiaoping and, in 1989, the Burmese Communist Party collapsed. This opened the way for ceasefire deals between the Burmese army and the communist militias and eased relations with China. Tight western sanctions were in place at the time and the World Bank and UN had cut off aid to Myanmar, which led the SLORC to turn to Beijing to develop the infrastructure it had promised in ceasefire deals, creating a favorable environment for Chinese aid and business. China began to pour billions of dollars into new infrastructure in Myanmar and set up hundreds of factories over the border producing consumer goods for the Burmese market. Today, Chinese businesses dominate much of Myanmar’s economy. Ceasefire agreements with other insurgent groups in the country soon followed. In Kachin, the Burmese army and the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) agreed a ceasefire that included jade mining concessions for military owned companies and crony businesses on both sides. Ceasefire capitalism and crony capitalism overlap.

A government-licensed company’s jade mining site in Hpakant, Kachin State, April 29, 2015. © Minzayar Oo/Panos Pictures.

Jade Mining

Kachin’s jade is found in a fifteen-kilometer-long belt of conglomerate rock along the Uru River centred on the town of Hpkant. The conglomerate was transported and deposited over thousands of years from primary jade dikes on the Tawmaw Plateau to the northwest. These deposits are of the jadeite variety, a rare, harder, and more valued form of jade than the softer, more common variety, nephrite. Imperial jade, distinguished by its color and transparency, is the most valuable of all jade varieties and has only ever been found in the Kachin deposits. The main source of demand for Myanmar’s jade is China, where the stone has assumed great cultural importance over the last 5,000 years. In Confucius’s Book of Rites, jade was associated with no less than eleven virtues—benevolence, justice, propriety, truth, credibility, music, loyalty, heaven, earth, morality, and intelligence—giving it symbolic and quasi-mystical powers as well as monetary value.

Kachin jade has been mined and traded with China since the thirteenth century, but significant extraction only began in the second half of the eighteenth century when Yunnanese traders transported it from Kachin along mule caravan routes that formed part of the ancient Silk Road. During British rule, jade mining was regulated and overseen by an Administrator of Mines, but because jade was of no interest to the British (their primary interests in Burma were teak, oil, and rice), the jade trade continued almost unhindered. In the 1960s, jade mines were closed to foreigners and private mining, and the trade of gemstones became illegal. The introduction of the Myanmar Gemstone Law in 1995 allowed jade extraction and trade to begin again. While Western nations boycotted Myanmar, China re-opened its borders and trade between the two countries exploded. As a result, jade mining increased exponentially, officially generating an estimated US$122.8 billion between 2005 and 2014, and US$31 billion in 2014 alone when production peaked, an amount equivalent to forty-eight percent of Myamar’s GDP.

The growth in revenue from jade mining was partly due to the transformation of the mining process itself, which until the 1990s had been small scale and artisanal. Once Myanmar’s military became involved, mining processes were mechanized and operated at an industrial scale. Dike and blast mining were introduced on the Tawmaw Plateau, sophisticated equipment was brought in for mountaintop removal, and large-scale boulder and gravel mining continued in the Uru Valley. All of these techniques required significant investment and squeezed artisanal miners out. However, industrialization attracted a surge of unregistered jade diggers known as “hand-pickers” or yemase (meaning unwashed stones) from around the country to eke out a living by picking out jade from mine tailings. Up to 200,000 of these young men between the ages of sixteen and thirty live in makeshift tents around the mines during the dry season when formal mining operations are underway, shrinking to about 5,000 during the rainy season. Their work is highly dangerous as tailings are enormous, unstable, and prone to liquefy and collapse in the rain. The deadliest such accident to date occurred in July, 2020, when tailings collapsed into a lake formed by monsoon rains and created a wave of mud and water that swept 174 miners to their death and left 100 unaccounted for. As well as its human cost, industrialized mining has rendered the Uru Valley unrecognizable. Excavation and drilling has fissured the earth and turned mountains into craters. This is visible in satellite imagery, with scars in the landscape appearing in the 1990s and accelerating from the mid 2000s onwards. The Uru River, once flowing freely through the Hpakant Valley, is now obstructed by mining waste and severely polluted.

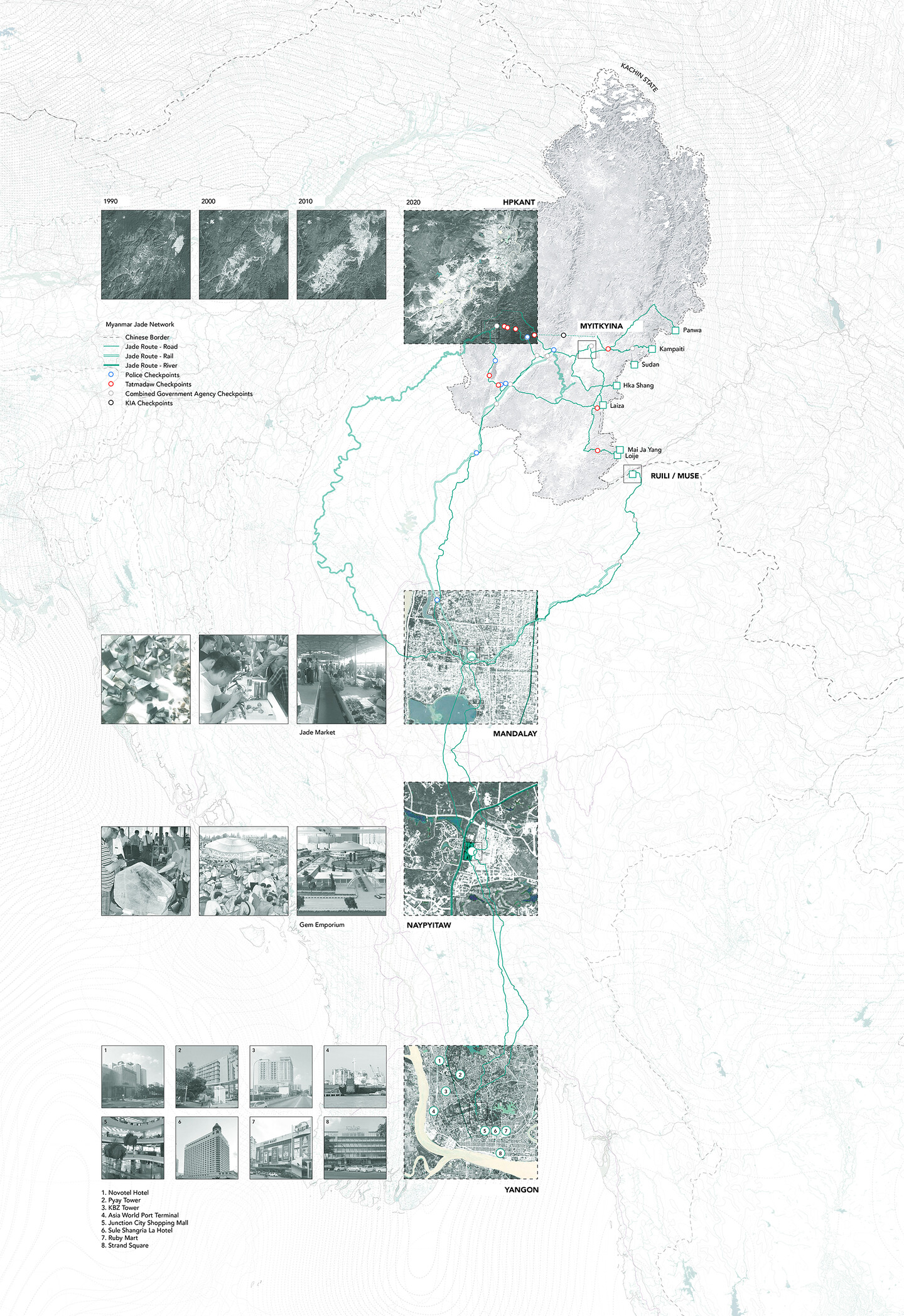

Nodes in the jade distribution network. Map by John Cook, 2020.

Distribution Networks

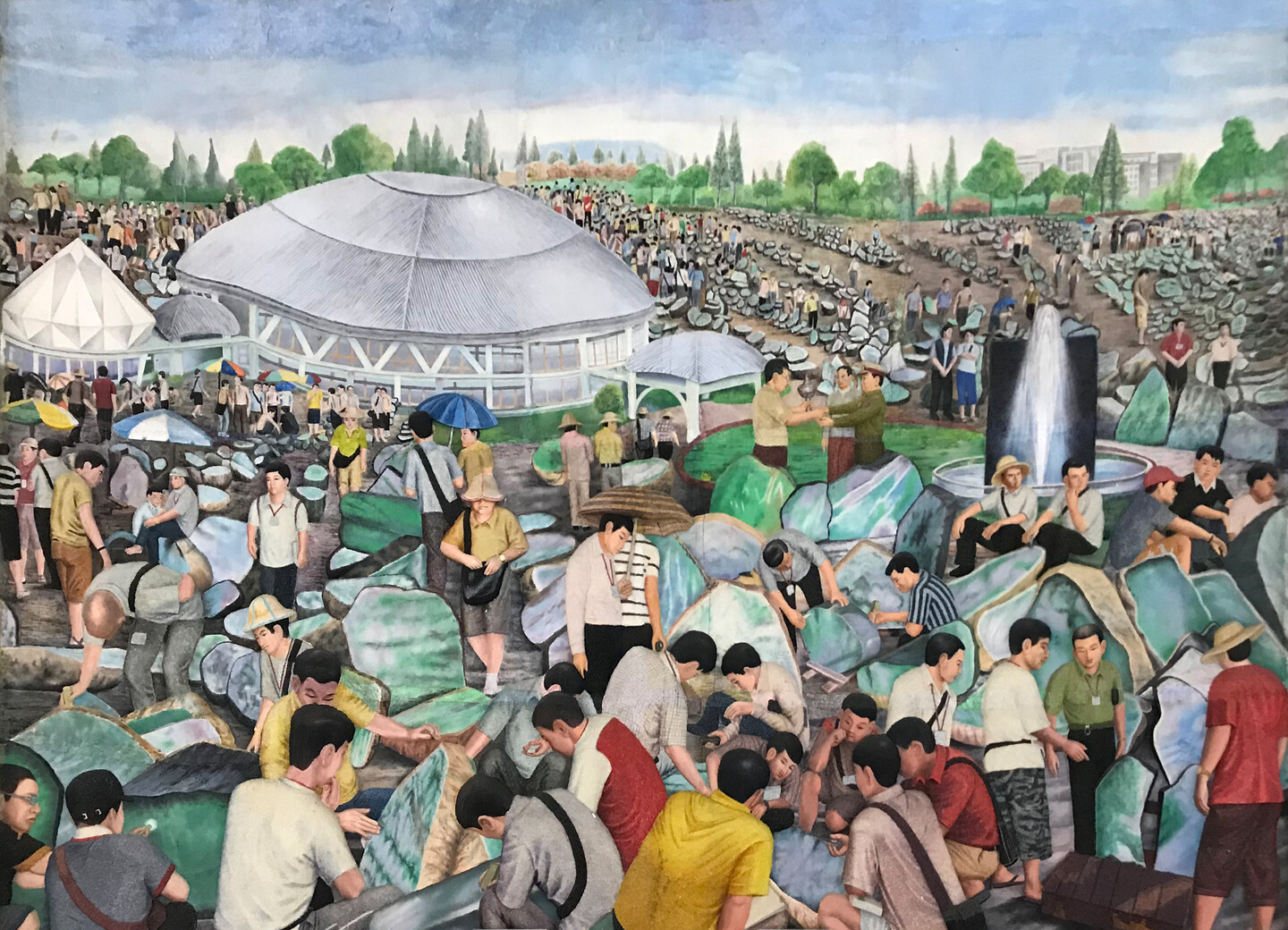

Once mined, jade has many routes into Chinese markets. The only legal way to buy unprocessed high-quality jade from registered sources is at the official government emporium in Naypyidaw. The official Gems Emporium is held once a year in Mani Yadana Jade Hall, during which time jade sales spill over onto a vast parking lot adjacent to the main building. Emporium sales are subject to tax, and only after stones are taxed can they be legally exported. Lower-grade jade can be sold legally at jade markets in Mandalay and Yangon. The biggest of these is the Mahar Aung Myay Market in Mandalay, which during peak periods hosts an estimated 40,000 buyers and sellers in a sprawling, crowded labyrinth of arcades accessed through heavily guarded gates. Yunnanese and Chinese brokers inspect stones for their quality with small flashlights and communicating with buyers in China via WeChat and live video streams. The arcades overflow into endless market floors where jade and other stones are laid out for sale, and which lead into back-of-house cutting and polishing operations.

Painting of the annual jade emporium in Naypyidaw, artist unknown. Photograph by Lindsay Bremner.

To avoid the costs incurred via legal routes, companies smuggle an estimated fifty to eighty percent of their jade directly to China, bypassing official controls on both sides of the border. There are two main routes for this: via Myitkyina, the capital of Kachin State, and along dirt paths, rivers, and roads to a number of small towns along the Chinese border; or from Mandalay via Muse, the capital of Shan State, to the Chinese border town of Ruili. Ruili is the largest of the Chinese border towns and a key hub for jade and drugs. Burmese historian Thant Myint-U visited it in the 1990s, when it was a small and backward place, selling very little except Burmese jade (even then) and other contraband. When he visited it twenty years later, it was a town of wide palm-tree-lined boulevards and glass fronted shops selling Armani and Rolex. The expansion of the jade sector had not only transformed the city into a hub for the processing and exchange of jade, but also a convenient place to launder money. With major private sector investment in construction and infrastructure, property development was booming (property prices were said to be equal to those in Shanghai or Beijing).

Jade valuation in the Mahar Aung Myay Market, Mandalay, 2019. Photograph by Lindsay Bremner.

Jade Urbanism

Significant changes to Myanmar’s Property Tax Law in 2007 reduced real estate taxes from a prohibitive fifty percent to twelve or fifteen percent and removed the need to demonstrate origins of income. These amendments made it easier for illicit capital to enter the real estate market. Those who had made undocumented fortunes seized the opportunity to convert cash into real estate. Changes in the Property Tax Law preceded the shift of the nation’s capital to Naypyidaw, a lucrative move for crony companies such as Asia World, Max Myanmar, and the Htoo Group, who were awarded contracts for its construction. The relocation of the capital to Naypyidaw enabled the sale of the land and vacant buildings in Yangon, which government ministries and departments owned or in which they were formerly housed. Beginning in 2010, hundreds of government properties were put up for auction. This sell-off, the largest in the country’s history, was taken up by military elites and crony companies, consolidating their economic position in advance of the 2011 elections.

Many of the high-profile new developments that we witnessed in Yangon were closely tied to these developments. Ruby Mart, the first shopping mall built in Yangon on the corner of Pansodan Street and Bogyoke Aung San Road, is owned by the military conglomerate Myanmar Economic Holding Limited (MEHL) and stands on a site that once housed the Ministry of Commerce’s Myanmar Agricultural Produce Trading. MEHL controls large tracts of the best Kachin jade land, with many of the main jade mining companies in Hpakant working as its subcontractors. The crony company Asia World Group, run by Steven Law (the son-in-law of Lo Hsing-han, a 1970s opium warlord), worked with the Yangon Development Committee to upgrade Strand Road in downtown Yangon and improve access to its Asia World Port Terminal, which handles a large proportion of Yangon’s cargo. Asia World also financed and built the luxury Sule Shangri-La Hotel on Quartermaster General Office-owned land on the corner of Bogyoke Aung San and Sule Pagoda Roads. Asia World Group is one of the largest companies in Myanmar and formerly operated the Hpakant jade mining company Yadanar Taung Tann Gems. The Kanbawza Group (KBZ) owns Strand Square, an office complex in the center of Yangon’s financial district. It operates and owns the biggest private sector bank in Myanmar, KBZ Bank, whose branches pepper the country. A company brochure in 2017 featured images of KBZ mines in Hpakant and details of jade sales at official emporiums amounting to millions of dollars. According to the KBZ senior managing director, “jade mining is the company’s first business and a prime and legal source of income for other businesses in the conglomerate.”

Another crony company, Max Myanmar, owns Yangon’s 366-room Novotel Hotel and acquired a sixty percent stake in Pyay Tower, a prominent state-led development that includes a shopping center, offices, and apartments. Max Myanmar initially made money importing cars to Myanmar before consolidating ties with the military. It ran the Moe Pin mine in Kachin, a joint venture with Myanmar Gems Enterprise, where the largest piece of high-class jade ever found in Myanmar was discovered in 2010. Another company, the Htoo Group, is developing of a 21.9 acre site in downtown Yangon that will include a four-star hotel, an apartment complex and a shopping mall. Htoo Group is owned by Tay Za, who was the chairperson of Myanmar’s Association of Gem Industries for six years from 2008 to 2014. The list of real estate ventures by crony companies could go on and on, but even this abbreviated one confirms the links between cronyism, jade, the state, and glittering real estate ventures in Yangon. Often built as favors to state authorities in return for further concessions, real estate became a way of offloading cash and consolidating influence while catering to the consumptive lifestyles of ultra-rich business elites.

Mynamar in China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Map by John Cook.

Many of Myanmar’s military conglomerates and crony companies today are diversifying their business interests away from jade towards the infrastructure and energy sectors, which in Myanmar are dominated by Chinese interests. While mining jade for Chinese markets will continue to be lucrative, getting in on the act of servicing China’s energy needs will be more. As part of its Belt and Road initiative, China has planned an economic corridor running from Kunming, the capital city of Yunnan, through Ruili to Mandalay. From Mandalay, the corridor forks southwards through Naypyidaw to Yangon and westwards to Kyaukphyu in Rakhine State. In Yangon, an agreement has been signed by the Yangon Regional Government with the Chinese state-owned China Communications Construction Company to build the infrastructure for New Yangon, a 8,000-hectare development west of the city, in exchange for 2,800 hectares of land there, which amounts to thirty-five percent of the land available for development. In Kyaukphyu, a new SEZ, oil terminal, and deep-sea port is under construction. Kyaukphyu has enormous strategic value to China. It will provide landlocked Yunnan access to the Bay of Bengal, resolving what President Hu Jintao called the “Malacca Dilemma” and strengthening China’s presence in the Indian Ocean. The corridor includes ports, highways, railways, and power plants and, more importantly, a 2,380-kilometer pipeline to transport oil and gas from Rakhine to China’s inland mega-city, Chongqing. Crony companies including Asia World Group, KBZ and Max Myanmar have already been awarded infrastructural tenders along the corridor. It has been suggested that one of the motives for the Rohingya displacement in Rhakine State was to clear the land for these operations and enable easier access to the state’s resources. China is thus not only consolidating its power over Myanmar’s political economy and transforming its territory, it is ensuring that Myanmar’s resources are further aligned with its strategic interests in the region and beyond.

×

Fieldwork for this essay was conducted as part of Monsoon Assemblages, a research project supported by the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant Agreement no. 679873). The essay is an extract from a chapter in the book Monsoon as Method, Actar, 2021.

Accumulation is sponsored by the PhD Program in Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania Weitzman School of Design.

Lindsay Bremner is a research architect in the School of Architecture and Cities at the University of Westminster, London.

Beth Cullen is an anthropologist and postdoctoral research fellow in the School of Architecture and Cities at the University of Westminster, London.