What’s Better About Using Estimated Securities or an IRA? Here is a calculator to answer the question.

Volunteers at Habitat for Humanity in Culver City, California. (Photo by John Wolfsohn)

Getty Images

The 2017 Tax Act, with its huge standard deduction, did serious damage to the tax benefits of philanthropy: For many taxpayers, donations no longer cut the ice on a tax return.

There are two counter-movements. One option for donors who are old enough is to use an IRA to fund charitable donations. The other option, which is good at any age, is to pool several years of donations into a single large contribution to a donor-advised nonprofit fund.

So what’s better at tax time, the IRA donation or the donor advised fund? It’s a tough question, and the calculator that accompanies this story provides numbers for comparison.

To simplify the answer, the IRA approach is often the best for people who are making mandatory withdrawals from their retirement accounts and are nowhere near the standard withdrawal threshold. The donor fund may be better suited for taxpayers who have valued securities they’d like to get rid of and who are already near or above the hurdle.

This is a consequence of the November elections. Under current law, valued assets receive a “step-up at death” that bypasses capital gains tax, and this makes it smart to go to the grave with the best performing stocks. But President Biden and his acolytes in Congress want to remove this tidbit.

If you were planning on leaving your grandchildren with some Amazon stock that you bought decades ago, think again. Given the likelihood of a step-up not surviving, it might make sense to use these stocks for charity. Biden does not threaten to fill the other valuation loophole: bypassing capital gain on donated assets, including assets donated to a donor-advised fund.

Both of these nonprofit strategies have been around for a while. The IRA donation, which is allowed to account holders over the age of 70-1 / 2, was introduced in a 2006 tax law. The donations go back to the founding of the charitable gift fund Fidelity Investments in 1991. Since then, Fidelity customers have used this fundraising pool to donate $ 51 billion to 170,000 charities.

Hosannas receive both strategies from financial advisors. But ask a counselor which of the two is better and you might get a shrug. Well, it is complicated, you will be told.

Donation calculator

Forbes

It is save. The IRA tactic works because it keeps otherwise taxable IRA payouts completely out of your income stream: your custodian sends some of your money to a charity instead of sending it to you.

Without the 2006 law, you’d have to first take money out of the IRA, deposit it into your checking account, and then send your own check to the charity. This would not be a wash. The deduction that could offset IRA income would be of no use to you if you claimed the standard deduction. And even if the taxable income from the IRA payout were fully offset, you would be worse off for another reason: the transaction would increase your gross adjusted income, potentially increase your Medicare premium, and cause other damage to your tax return.

Name the IRA’s “qualified charitable distribution” a loophole if you’d like. It is intended. It gives retirees a big push towards generosity. And it’s not for the super rich: there’s an annual limit of $ 100,000.

Another reason to use an IRA to make a charity contribution is so that those distributions count towards the minimum required withdrawals from the IRA, which begin at age 72. Taxpayers who do not need their IRAs to live will want to maintain this IRA housing for as long as possible.

Against this background, the donor fund option has two reasons. One of them is that it is a way to group gifts that have been going on for years into one large print so that you can get some benefit from the print while still using the standard print for most of the years. You can then take the time to distribute the money.

The other good thing about a lender-advised fund is that it can be combined with that second gap in terms of valued assets. Donations of valued assets held for more than a year are fine for a single deduction valued at today’s price, but the increase in value is never taxed.

Imagine the hypothetical taxpayer Harry at the age of 72. He wants to send $ 5,000 a year to an anti-poverty group he works with. He has a large IRA that he doesn’t have to resort to because he has other assets for retirement. He also has a $ 50,000 equity position that was bought for $ 6,000 years ago.

There are two ways Harry can fundraise a decade.

Method I:

Harry donates the shares to Fidelity Charitable or to one of the copycat donor funds found at other brokers. That gives him an individual deduction of $ 50,000 and saves him (or his heirs) any income tax on the $ 44,000 increase in value.

Unfortunately, not the entire individual deduction is used to reduce Harry’s tax burden. His standard deduction (return together, two seniors) is $ 27,800, and he is only allowed to deduct $ 10,000 in state and local taxes. That means the first $ 17,800 of all other broken down prints won’t move the needle. With no other deductions (his mortgage paid back), he finds that only $ 32,200 of the donor fund contribution reduces his taxable income.

The donation fund will cover ten years of Harry’s usual contributions. Payouts start at $ 5,000. If the account is invested in a stock index fund that generates a 5% return, the charity will raise a total of $ 60,700 over the decade. This number reflects a 0.6% annual fee for running the donor account, as well as a small fee for the index fund in which the money is invested.

Method II:

Harry sticks to the stock. Instead, he makes contributions by directing his IRA custodian to send money to the charity, starting at $ 5,000 in the first year and increasing the amount to reflect the profits from the stock index fund in his IRA. Assuming the same 5% stock market return, the charity will do a little better with a cumulative profit of $ 62,800. This is because the IRA does not incur an administrative fee for running donor funds.

Which form of giving is better? For Harry and his heirs, the IRA route is the right one. The family will ultimately be better off doing $ 7,700 this way than a $ 50,000 donation plan.

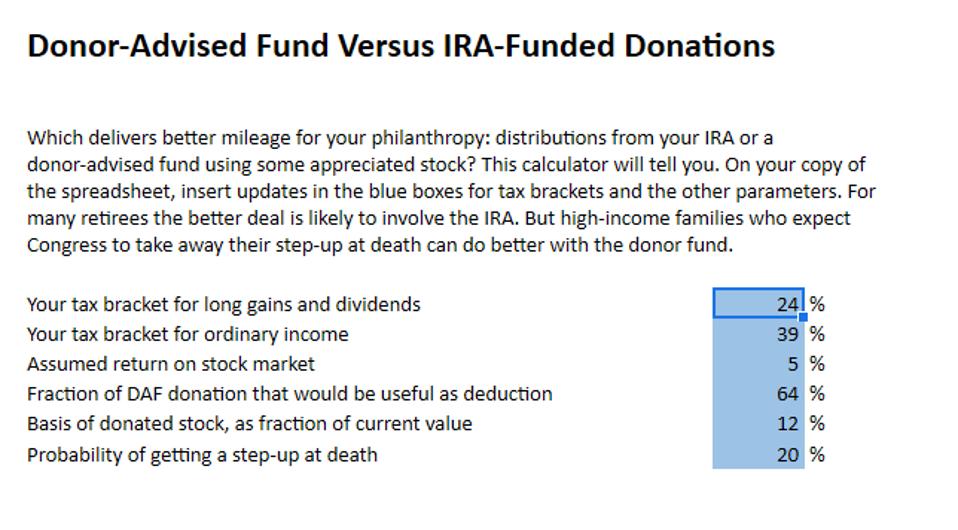

Access the calculator by downloading it from this link. To change the parameters, make a copy of the file and work with the copy. (You cannot change Harry’s file.)

For Harry, we assume a marginal tax rate of 39% on ordinary income and 24% on stock dividends and long-term capital gains. These rates include state income taxes, the 3.8% surcharge on investment income, and the Medicare premium income penalty.

Other Assumptions: The stock market has an annual return of 5%; Only 64% of the deduction for setting up the Donor Fund would be used to reduce Harry’s taxable income. The stocks Harry could use for the donor fund have a cost base equal to 12% of their present value. There is a 20% chance Harry’s heirs can benefit from a step-up.

Please note these rules for funds advised by donors:

– Once the money is in the fund, you need to use it for charity.

– There is no time limit on how much money can be withdrawn, but leaving it idle for a long time is a bad idea as it will be eroded by the 0.6% fee.

Rules for IRA gifts:

– You are eligible on the day (not the year) you turn 70-1 / 2 years old.

– You cannot transfer money from an IRA to a fund recommended by donors.

– If you want to credit a donation towards your required annual payout, it must be made before this payout.

– The unused portion of your $ 100,000 annual donation limit cannot be carried forward.

– Your recipients must acknowledge the gifts and, just as with checks sent directly from you, state that they did not receive any benefit.

Try that out calculatorUse your own tax rate assumptions and make your own handicap as to whether your heirs will enjoy the top-up. The Biden tax plan provides a $ 1 million tax exemption on gains from taxation on death, but it is unlikely to be indexed for inflation.

The calculator doesn’t predict a dollar outcome – who knows how long you’ll live or what the stock market will do? It’s just meant to highlight the difference between two ways to help this soup kitchen.

To compare two very different sequences of cash flows, the calculator assumes that cash is invested in a stock index fund that is liquidated at the other end. In particular, it is assumed that: the donor is now required to initiate mandatory withdrawals from an IRA; The IRA will remain in his or his spouse’s hands for 18 years and then go to children who keep them going for a maximum of ten years. The donor keeps payouts to a minimum and invests them in the index fund after tax. The tax advantage from setting up the fund advised by donors is invested in the index fund. The formulas also include a small wedge between the income tax rate and the deduction tax rate; This has to do with the Medicare grave and other pitfalls involving an adjusted gross income.